The housing affordability crisis in Australia is a product of the cause and effect of numerous factors including the way we fund and build apartments on multi-residential developments.

But emerging financial models may help ease the pain.

The word baugruppen means ‘building group’ in German. It is also the name of a new funding model promising savings of up to 30 per cent on the cost of housing for multi-residential development buyers.

Baugruppen the model is attracting the attention of home buyers priced out of the market as well as banks interested in its claims to reduce one of the most significant risks in multi-residential construction.

Settlement risk is when off-the-plan apartment buyers, usually investors, change their minds at the last minute. This is generally because the value of the property upon completion of construction is lower than expected.

Instead of paying for their apartment, they walk away.

Typically, about 3 per cent of buyers walk away from their purchases but the number can rise in an apartment building glut like the one we are seeing in big cities such as Melbourne. In June 2016 the figure had risen to 5 per cent, according to a law firm Maddocks.

One innovative financial model in apartment funding is the Nightingale model. The model is non-profit, with no developers or real-estate agents playing a part.

Melbourne architecture practice Breathe initiated the model then formed an independent, not-for-profit organisation, Nightingale Housing. This organisation raised funds from banks and investors for two multi-residential developments – The Commons and Nightingale One.

The apartments sold for about 15 per cent under market value and both developments achieved 100 per cent presales.

So what did Breathe get out of it?

A commission to design the block with a group of buyers excited about common ideas: community, sustainability and housing affordability.

Significant

The newest Nightingale project encapsulates an entire precinct in Brunswick. Seven architecture practices are involved, each designing a multi-residential apartment block and offering another level of saving for some buyers.

Two of the architecture practices hope to use an innovative Baugruppen finance model developed by a consulting company, Urbau.

Urbau founder Duncan McGregor says this is model was developed exclusively for Nightingale projects.

“Nightingale targets 15 per cent less than market prices; we can target 30 per cent less. The difference is significant,” he says.

But Australians prefer not to live in apartments; they want houses. They love them – they commit time, energy and pride to them.

That’s one reason suburban homes are more valuable than apartments.

Those emotions are bankable meaning in purely economic terms; our emotional investment makes settlement risk in suburban dwellings low. By contrast, investors buy 85 per cent of new apartments built in inner-city Melbourne.

When just two or three investors walk away from a settlement they gouge the profitability of multi-residential developments.

Banks and investors charge a premium for the risk, which drives up the cost of funding and, therefore, the price of the apartments. The Baugruppen model reduces the risk; buyers are emotionally invested in the apartments because they have helped fund and design them.

Close to 5,000 people registered their interest in the latest Nightingale project – which will provide about 280 apartments – significantly reducing the risk and costs.

How does it work? Let’s look at a typical multi-residential development first. Banks stump up 70 per cent of funding and investors provide the rest at high-interest rates. In many cases, 30 per cent interest is not unusual.

For the first two Nightingale projects, the group secured bank funding at the usual rates but found socially-conscious investors prepared to lend for lower interest rates of 15 per cent.

Baugruppen aims to replace some or all of the investor funds with money from the buyer’s group, cutting down the overall cost of funding.

Several models are developing in Australia. Geoffrey London, a former chief architect of both Victoria and Western Australia, is part of a group working pro-bono to foster a Baugruppen project in White Gum Valley on the fringe of Freemantle with support from the state government.

If London can bring together a group of buyers for the 16 to 19 dwellings planned for the land, the state government won’t expect the buyers to pay until the project is built.

The White Gum Valley development has several goals:

- To create affordable housing;

- build better-designed medium-density apartments which are more sustainable;

- explore the potential of shared amenity; and

- increase a sense of community.

The downside for this project is the building group must provide about 25 per cent of the funding, a prohibitive contribution for many buyers.

Urbau’s Baugruppen model is more accessible, asking for only a 10 per cent deposit from buyers, with the other 20 per cent coming from Nightingale’s social investors.

Will it help?

The process is similar to buying land and engaging a builder. The difference is the building group buys land and constructs individual strata-titled apartments. The model also saves buyers GST and stamp duty.

McGregor is awaiting a final tax ruling from the tax office, but if all goes to plan, these additional saving will be passed on to buyers.

So what is to stop speculators selling as soon as the project is complete, pocketing the profit, and leaving housing affordability unchanged?

London says he has advised the Baugruppen buyers to discourage speculators.

“We have proposed to the group that they focus on owner-occupiers and discourage investors by inhibiting windfall profits for the first five years,” he says.

“Should a group member need to sell in the first year, they retain only 20 per cent of the profit, with the rest going back to the group. In the second year, the seller gets 40 per cent, then 60 and 80.”

Urbau’s model has harsher penalties for profit-harvesters.

All the Nightingale projects have a 20-year covenant which restricts profits, and McGregor will only work with Nightingale projects because he feels jaded from years in the traditional property development market.

So, what is in it for McGregor? Simply this – he gets paid a consulting fee. Neither Baugruppen nor Nightingale are about profits.

“Baugruppen is just something I am determined to see happen,” he says.

The risk for buyers

Sounding a bit too good to be true? There are three main risks.

Unlike a traditional deposit for an apartment – which is held in a secure account by a solicitor – the Baugruppen funds are used in construction.

If the project were to fail, there is no guarantee that the funds could be returned.

With 40 people on the title (the maximum allowed), there is a risk that individuals go bankrupt or fall out with others in the group.

“The land transfer is signed so that, in the event of a default by a participant, they can be replaced by another participant,” McGregor says.

This protects the development as a whole but not necessarily the individual. Otherwise, defaulters might force the project to sell the land.

This clause is a fascinating element of the Baugruppen model.

While demanding high levels of trust, it’s not in Nightingale Development Company’s interest to use such a clause to “ruin” people, McGregor says.

The clause protects the group from an individual buyer who works against the group’s interests.

McGregor calls it “a**hole insurance”.

The final risk is that development costs are unpredictable.

“We can’t say from day one what your apartment is going to cost,” McGregor says. “Participants sign up for a contract price which is the estimated cost of the apartment plus 15 per cent.”

“The only reason the profit is there is if you show banks a spreadsheet with zero profit, they won’t fund it. But any profit that remains once all costs are paid is returned to the buyers.”

McGregor says buyers need to offset these risks against the inherently reduced risks of the Baugruppen at Nightingale model.

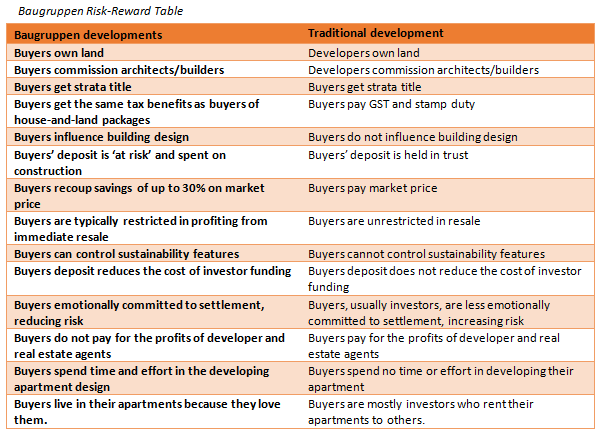

Compare the pair

In essence, the Baugruppen model is an experiment based on a precedent in Europe and many groups are banking on its success.

These include:

- Architects, because they prefer to work directly with home buyers than through developers.

- Buyers, because it lowers the price of their apartment (and potentially prices generally) and lands them among like-minded neighbours.

- Banks and investors – because of the reduced settlement risk, especially in a market glut.

- Planners – because they need city dwellers to start loving multi-residential developments to stop urban sprawl.

The only real losers are the tax department, developers and real estate agents who get nothing from it and stand to lose more if the model succeeds in reducing housing prices.

Such developments might remain the purview of the middle classes, who have the money, education and time to grapple with a new model.

In Europe Baugruppen peaked at 20 per cent of the total development market and has since fallen back to around 10 per cent. On such numbers, it’s an alternative and not a threat.

Suburban Baugruppen

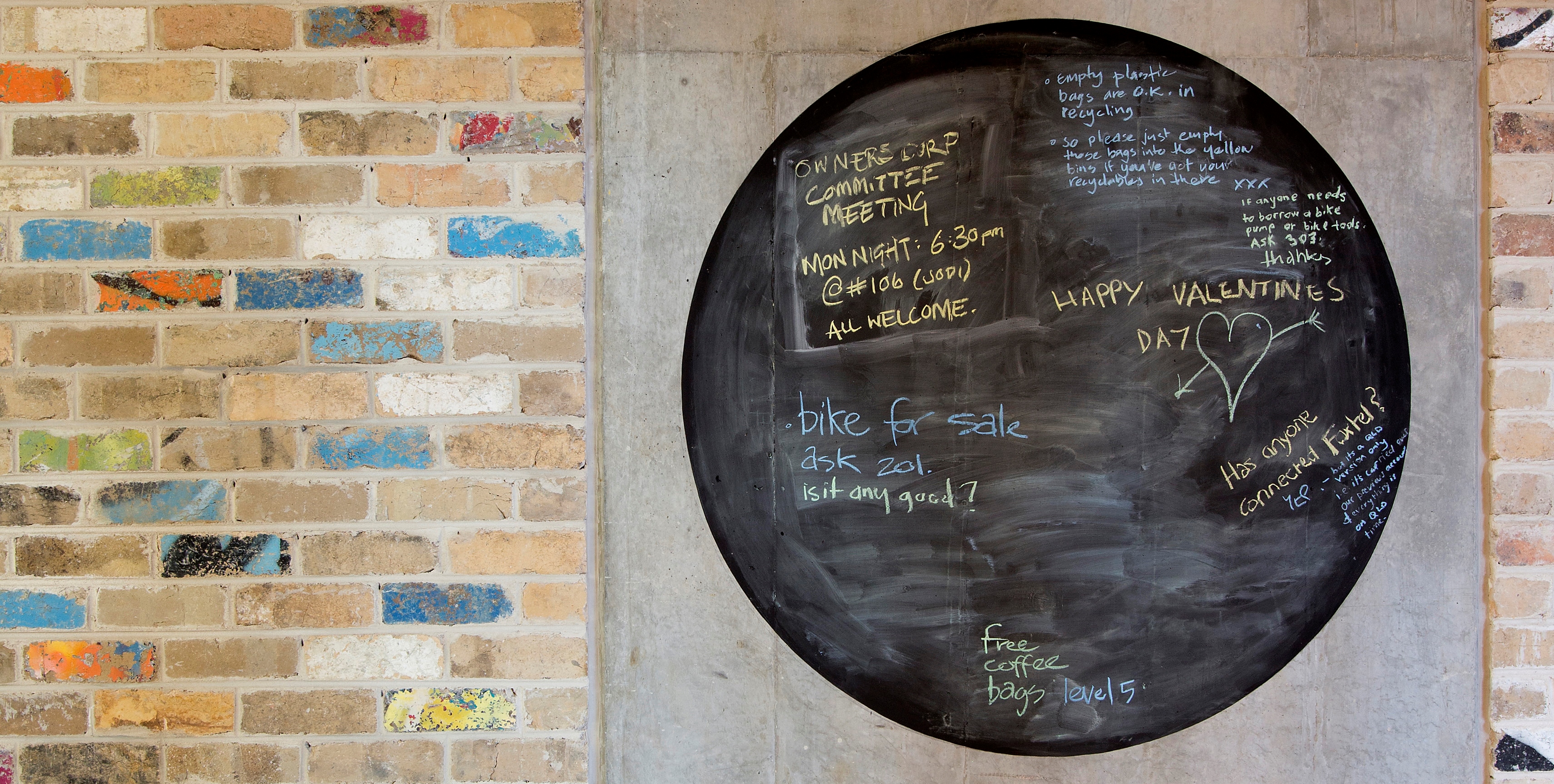

Baugruppen building groups can form around any set of common interests but they typically form around energy efficiency and sound design principles.

In part this is economic; such designs reduce ongoing energy costs. In part, they attract left-leaning buyers.

The Green Swing is a small-scale suburban developer which pioneered building three dwellings on a single suburban block in Perth.

The success of this initiative attracted media attention, public speaking opportunities for co-founder Eugenie Stockmann, who now runs workshops on sustainable co-operative housing. She says people make different decisions as homeowners.

“When I ask people if they would put solar panels on their roof, everyone puts up their hand,” Stockman says. “Then I say ‘now you are an investor’.”

“Suddenly, they are asking ‘would I be able to sell the house for more, could I charge more rent, what is the return on investment?’ for something that is a no-brainer.”

Stockmann now runs a website fostering cooperative housing projects, called Green Fabric. The idea is to connect buyers with cooperative, sustainable housing.

“While housing affordability is a key driver, what’s interesting is that owners take a long-term perspective,” Stockman says.

“It is not just the cost of building; it is about how easy is it for me to get around, are there car share schemes? It includes a whole lot more.”

This story was first published on ANZ BlueNotes. Visit ANZ Bluenotes here.